Artist Interview: Eric Stewart from 10cc-The Things We Do for Great Records

By Marsha Vdovin

There's nothing like the voice of experience. The legendary English band 10cc is best known for their hits "I'm Not in Love" and "The Things We Do For Love." I was floored to get an email from 10cc's Eric Stewart saying how much he liked the Universal Audio Helios 69 plug-in that we recently released, and was even more psyched when Eric mentioned how he used Helios boards for years and that our UAD emulation was the real thing.

10cc was formed in 1970 by singer/guitarist Eric Stewart, a former member of The Mindbenders; singer and guitar/bass player Graham Gouldman, ex-Mockingbird and composer of songs for The Yardbirds, The Hollies, Jeff Beck and Herman's Hermits; and the former art students and multi-instrumentalists/singers Kevin Godley and Lol Creme.

I interviewed the charming Eric Stewart on the phone at his home in France for this month's artist interview.

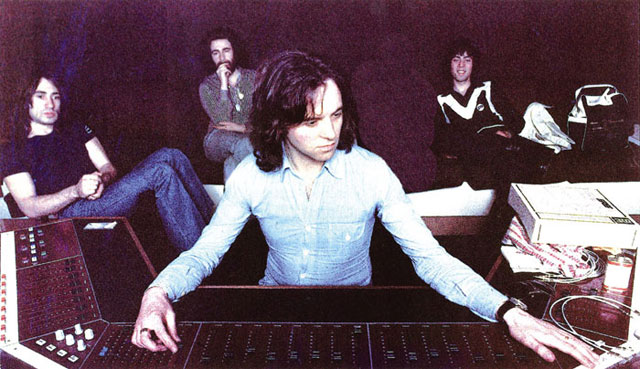

|

| 10cc in Strawberry Studios, 1975. From left: Lol Creme, Kevin Godley (at rear), Eric Stewart, Graham Gouldman. |

How did 10cc come about?

I'll give you a very brief description of how the band came together. That's quite simple. I started Strawberry Studios in Stockport, Manchester, around about 1968--my spell with Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders. We had a little band called Hot Legs, which was myself, Kevin Godley and Lol Creme. We used to just do session work for people in our studio, which was Strawberry Studios. After working quite a lot with other people, we had a manager who eventually suggested, because we were all performers and writers, that we should do something ourselves.

There are many descriptions of what 10cc means . . .

At that point in time, Graham Gouldman joined us--he'd written a lot of hits for The Hollies, Yardbirds and Herman's Hermits, who were especially very big in the States. We sat down together, started to write, just to see what we could come up with, and the first thing we did record was a sort of '50s doo-wop rip-off song called "Donna." We took that to all the record companies in London, and everybody bar one turned us down.

There was a guy called Jonathan King, whom I think had some minor hits in America, with a group called Headchoppers Anonymous. Anyway, he started his own record label called UK Records, and I remembered him from the '60s, so I took this track to him, and he said, "It's wonderful, it's a hit record. Yes, I'd love to sign a deal with you. What's the band called?" We didn't have a name, and he'd had a weird dream the night before. There are many descriptions of what 10cc means--he's got this very vivid imagination, and he came up with the name 10cc. I said, "Yeah, why not? It's a short, clip name, easily memorable, so why not?" And that's how10cc was formed!

There was so much creative energy. Was it hard to manage all that? Was there a battle of egos? How did songwriting happen?

Most of the songwriting was from two pairs. 10cc was a pretty unique band, actually, if you think about it. I don't think there was another band, even The Beatles, where you have four writers capable of writing a Number One record, and capable of singing a Number One record, which we did many times. You're right. To pool all that talent in one studio, one room did get egos going, but actually in an incredibly constructive way.

I don't think there was another band, even The Beatles, where you have four writers capable of writing a Number One record, and capable of singing a Number One record, which we did many times.

We did have these funny sessions of arguing about things, but it was very progressive somehow. We didn't soil the merchandize at all by arguing about it. And hits like "I'm Not in Love" came together because of this tangential thinking of different members of the band wanting to do something different, and really holding out to do that. So the talent, I suppose for the first four albums, worked very, very positively. We just kept recording, writing, recording, and it was fantastically constructive during that period in our history. Gosh, we were writing nearly two albums a year, and trying to tour as well on top of that … and break markets! America took us a lot longer, but we got a couple of major hits there, a couple of Number Ones. We managed to do it.

I suppose after the "How Dare You?" album, the egos started to work in a negative way, and we started to really argue with each other. Right about 1977, after our biggest album, The Original Soundtrack, which did contain "I'm Not in Love," it started to fragment a little. Godley and Creme left the band at that point, and Gouldman and I carried on with 10cc, and got some even bigger selling records, actually. I think "The Things We Do for Love" was bigger in America than "I'm Not in Love."

You did so much innovative recording. Was a lot of the songwriting happening in the studio?

Yeah. We wrote more in the studio than we did outside. Occasionally you would have meetings outside, at each other's house, maybe, just to discuss an idea, but the songs seriously developed in the studio. We had a very good deal with each other, that no matter who wrote the song, we split the royalties four ways. It was fabulous, because it cut out any crap where somebody would say, well, look, you've got six songs on the album, and I've got to earn a living, and I want four of my songs on the album. We never had that sort of conflict, which I believe many bands did. You'd get the drummer, or the bass player, or somebody who couldn't write a song insisting that he had a song on the album. And it was usually mediocre. It didn't happen with us. We just used what we thought was best--the best track. It didn't matter who wrote it, and we split the money four ways. A very, very constructive idea, and it certainly worked for us.

What were some of your favorite studios to work in? Or did you always work in your own studio?

10cc did record everything at the two--we built two Strawberry Studios, one as I said in Stockport, near Manchester. The second one we built just before Godley and Creme split away. We built one down south of London, a place called Dorking, which is about an hour away from London. But studios before that, my favorite studio of course was Olympic. I recorded there with The Mindbenders, with John Paul Jones producing. He of course, was the bass player with Led Zeppelin.

Oh, he's a brilliant guy...

Oh, he's a fantastic guy, isn't he? I loved him. And he produced a couple of songs, a couple of hits, with The Mindbenders. We did a cover version of The Boxtops' hit, "The Letter," which John Paul did. A couple of other tracks as well that we'd written ourselves.

No matter who wrote the song, we split the royalties four ways. It was fabulous, because it cut out any crap . . .

But Olympic was fantastic. It was such a hotbed of music. You could walk in there, and the Stones would be recording in one of the studios. They would wander in and we would talk to each other. I borrowed Keith's guitar. Mick would come in and say, "I like that song, Eric." Or, "That's crap, what the hell you singing that for? [Laughs.] This stuff's so naff, man, what are you doing?" And then The Beatles came in to do things like "Taxman." Steve Miller came in to do his big hit. What was that called? "Jet Airliner," big old jet airliner--beautiful, beautiful track. Beautiful song. And a fantastic singer and guitarist. I love his stuff.

But as I said, Olympic had this fantastic vibe about it. It was three studios, just outside London. A place called Barnes. nd all the control desks were made by Dick Swettenham. Which brings us back to the Helios emulation that UA have just released. It was such a thrill to put something through it, because I haven't got those modules anymore. The first Strawberry Black 'Hybrid console, with the 16 Helios 69 modules is now scattered around the world. David Kean at Melontronics is restoring the Second Strawberry North console,the first Red Helios Wrap around design. To get that sound again, the Helios sound from a plug in, I thought, bloody hell, this is genius.

That's so wonderful to hear. That's why they work so hard on these emulations at UA. Did you have a Helios board at Strawberry?

Yeah. The very first board we did, we built a sort of custom-made board that had some pretty rubbishy mic amps in it. They just weren't good enough. And I remembered working with Dick down at Olympic, and I rang him, and I said, "Dick, would you please sell me some of your modules? I don't want the board, I want your modules. I want your mic line amps. And whatever faders you would recommend, too."

That's the basis of any good control desk, as far as I'm concerned. You've got a great mic line amp, and you've got a very good fader that doesn't color the sound at all, straight out from that--through nothing else--direct to the tape recorder. That's the way we did it. We built this hybrid desk, with 16 of Dick's modules, going straight out to an 8-track Scully. And the sound was so pure, unaffected by anything.

. . .to get that sound again. I thought, bloody hell, this is genius.

The warmth of Dick's modules, the 69 Helios modules, was quite phenomenal. I can hear it when I listen to our first two albums, the 10cc album, and then Sheet Music. The sound of those albums has got a lovely sort of analog warmth, that we've been trying to recreate in the computer field forever. And guys, Universal Audio, you've got it there! It's such a luxury to have it there in front of me now, without tons of wiring, and valves to go wrong, et cetera. I've still got a lot of my old gear. I've still got the UREI 1176s and 1178 stereo version. But I don't use them. I don't need to. This emulation in the UAD-1 cards is so good, I don't need to use them.

|

| The Helios Board at Strawberry Studios. |

That's so great to hear! I wanted to talk about how you recorded vocals, because you had this distinctive vocal sound, and compared a lot to The Beatles and Queen, a lot of chorusing. Did you have a basic vocal chain, did you do something different on every record? I also heard some story where you put microphones inside something that was moving around.

That wouldn't have been for vocals. But we did put a microphone inside a box with a music box in it, tinkering away. It's a special little thing we did on the end of "I'm Not in Love." There's a music box sound, but it's a microphone being swung around someone's head, with a music box strapped to it. It gave it a lovely sort of airy sound, as well. In the drum booth, at Strawberry, we did that.

That's the basis of any good control desk, as far as I'm concerned. You've got a great mic line amp, and you've got a very good fader that doesn't color the sound at all, straight out from that--through nothing else--direct to the tape recorder.

But for vocals, I was using Neumann U67s, the valve mics. And those were beautiful again, beautiful and pure. I think the old U47 was the ultimate vocal mic I've ever heard, it had a kind of distortion on it, and I mean a distortion. A distortion that was so tasty, and nice, it gave an edge to a voice. A little roughness on the edge, that if you ran it through an oscilloscope, you would say, "Mmm. That doesn't look good. It's not pure enough." But the sound was humanly very acceptable. So the Neumann valve mics were fabulous. I never used anything else. Tried AKGs, and apart from a very early C28 double stereo valve mic that was an absolute beauty, nothing ever got close to that pure, pure sound I loved.

With 10cc, again, we had the luxury of four very, very good singers. They could all sing. Everybody could sing, and everybody did sing on a hit record. It wasn't like having a novel voice in the band, like Ringo would be with The Beatles. You couldn't give Ringo a beautiful ballad to sing, for instance. It wouldn't suit his voice. And John's voice wasn't right with certain things. Paul's voice could sing rock 'n' roll or ballads so beautifully. And George had a fabulous unique voice as well. 10cc had four guys who could all sing a Number One record, and we did. So having the luxury of those, we had a very, very good broad harmony group there. Four guys with slightly different voices that really gelled together somehow quite magically. I can only describe like--like the Beach Boys. When you put those guys together. Wow! There's a set of frequencies there that somehow gel together, and don't get in each other's way, and it thickens the sound.

So whenever I did backing vocals, I got the four of us to sing, and my other engineer at the studio--a guy called Peter Tattersall--he would sit at the control desk while I went in there and sang with the other three guys, and we always double tracked the four of us, left and right, in stereo. And that just fattened the sound so dramatically. And that's all we needed. I had everything in there. We dropped in if there were bum notes or whatever, but most of the time, the harmonies gelled very, very well.

Did you use any UA hardware in those days?

Yes. The 1176 especially.

How did you use that?

We used it mostly to compress things like bass guitar and bass drum. It just fattened the sound out, without overloading the desk and the peak DM meters wouldn't go silly. It just locked the sound to a really nice fixed level, but kept its gorgeous warmth. Especially on bass instruments, as I said. I very rarely used them on vocals. In fact, on vocals, we very rarely used any compression whatsoever. I think eventually about that time dbx were bringing out some pretty good compressors. In fact it's something I've asked UA to see if they can emulate. That was the one I remember using mostly because I'd read that Donald Fagan was using it all the time on the Steely Dan tracks. In the early days, there was a very small company in Britain called Audio and Design, run by a sound designer called Mike Bevel. We had a couple of his compressors in the desk, and those were very tasty, too. But again, mostly on percussive-type of things, rather than vocals.

Are there any more interesting recording technique stories from "I'm Not in Love?" I'd heard that you did it all with tape loops, the backing vocals . . .

Yeah, we did. We tried to find a way to do the whole of the track with vocals, but not just like a capella vocals. It had to be something different, something that the Beach Boys wouldn't do, with all their massive, fabulous, fabulous harmonies and mulitlayering.

So what we did, we created a 13-track background noise, which contained a chromatic scale going from I think C2 up to C3 on a piano, and each of those chromatic notes had 16 voices recorded: three guys recorded 16 times on a 16-track recorder, then mixed down to a stereo loop. Then each of those stereo loops of 13 notes of a chromatic scale, were then jumped back into a multitrack, which was a 3M machine at the time, so we had 13 tracks full of guys just going, "aahhh," for like seven minutes. Taken from stereo tape loops that were 12 to 15 feet long, and were fed across the heads of an Ampex tape machine, and then around a mic stand with a capstan screwed on the top of it.

I've still got the UREI 1176s and 1178 stereo version. But I don't use them. I don't need to. This emulation in the UAD-1 cards is so good, I don't need to use them.

We made the loops like that purposely, because with that length, the edit, which for some reason always had a little blip, wouldn't be apparent if it happened every three or four seconds rather than every half a second or something silly like that. We created that backing track, so there are 624 voices singing the "aahhs."

That's brilliant.

That was 1975, so four of us had to physically get our hands across the control desk and each of us manned four faders of the 16, and as the chords of the song were changing, we changed the notes of those 13 chromatic scale notes that were on the multitrack. This all sounds very complicated, but it took us about three weeks to do it.

When we got it down, back to one stereo pair on the 16-track, with a blank track in the middle, we knew we had something pretty astounding, soundwise, and unheard of before. It just had a quality about it that I'd never heard, and never heard since. We sat there for days just listening to the thing, saying "Wow, what the hell have we recorded here? This sounds amazing. What are we going to do with it?"

I put the lead vocal on, quite quickly. When we got the stereo backing track recorded and mixed across, of these voices, we then erased the 13 tracks of voices and started to do the other work that was on that song. There's a piano solo, there's a bass solo. There are backing vocals, harmony vocals, my lead vocal, plus a Fender Rhodes, electric piano panned to one side with a seven-and-a-half ips repeat on the opposite side. The instrumentation was very, very simple. Just four instruments. But all those voices, that's what gave it it's weird color. It's a sound color, like a massive abstract canvas, if you like, of sound. It took us a long time to record it.

The song was about six-and-a-half minutes long, as well. We were told we couldn't release it as a single, because it was too long, and radio wouldn't play it. Eventually the BBC had to start playing it, because it got to 28 in the charts without them playing it once! And then they had to play it because it was a chart record, and then it went to Number One, and of course Number One in the States, too.

That is just a brilliant, amazing story. Did you ever replicate that process again, or was it just that one time?

Just that one time.

Amazing.

That's what 10cc were quite famous for. And it used to really, if you don't mind me saying, it used to really piss off the critics, because they couldn't pigeon-hole 10cc. We were not a doo-wop band, we're not a blues band, not a rock band and weren't a ballad band. Before "I'm Not in Love," the single before that was a rocker called "Life Is a Minestrone," just an out-and-out rock track, completely different. And most of the time we were entertaining ourselves in the studio, and just trying to do things different each time we started to record. So we never tried to replicate the 10cc voices again.

They still exist, and the tape loops still exist, and I've been working recently with David Keene, in Canada, who now owns the mellotron, the Mellotronics, and he's going to do some tape loops for the mellotron using the original tapes that I've let him borrow. He's going to make a set for me, of course. I couldn't set up a stereo analog machine now, because as you know, everything--we're recording everything to hard disk. I don't have a tape machine in my studio. It's all pure, pure Apple Macs.

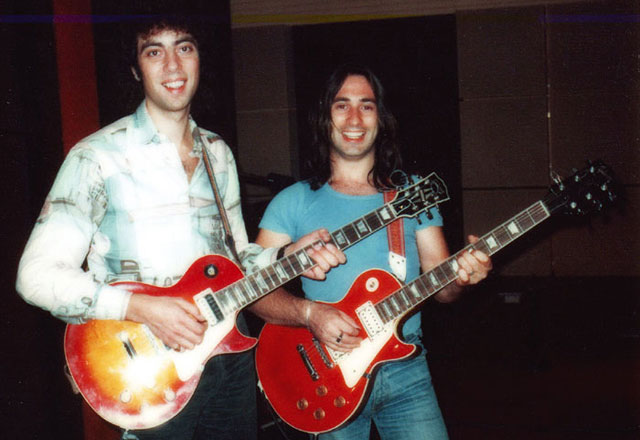

|

| Graham Gouldman and Lol Creme, Strawberry Studios, 1975. |

That leads to my next question: What's you're new studio like?

I've got fast Apple Macs, with tons of memory. I've still got my outboard gear there, just in case. I've got my UREI stuff, and I've got my AMS reverb, my AMS digital delays. I've got quite a few modern compressors, BBE and people like that.

What are you using has your host software? Your DAW?

Logic. Logic Pro.

And are you mixing in the computer? Do you have a mixing surface?

No. I don't mix in the computer. It's the only thing I allow myself. I'm using an analog board, which is--in fact it's called an Otari Status, and it's a pure analog board, with digital routing. It's a sort of very, very cheap version of a Euphonix board, but fantastic! I don't use the EQs or anything. I don't use the aux sends, nothing. Just pure, pure signal comes--as pure as I can get it--from the Logic, through the Mac, through a PCI card, out to MOTU--Mark of the Unicorn--24 in/outs. And I used a couple of those, so I've got the choice of 48 channels if I need them. Going to 48 channels on the Otari control desk and then that goes out to--well, nowadays I use a little Masterlink recorder to record my stereo back-tracks down to. Again, I read somewhere, Roger Nichols I think it was, or somebody saying that Steely Dan are using that now.

We had 13 tracks full of guys just going, "aahhh," for like seven minutes. Taken from stereo tape loops that were 12 to 15 feet long, that were fed across the heads of an Ampex tape machine, and then around a mic stand with a capstan screwed on the top of it.

What kind of monitors do you prefer?

Ah, the monitors, gorgeous monitors. They're Dynaudios, and they do this series called the Air series--Air 20s. They're not desktop monitors or anything like that, and they're not vast, big wall mounted monitors. They're sort of in between. Three-way monitors. Good, good bass, good midrange… fantastic high end. They're so pure, and so clean, no matter what volume I've got them at.

I try to do most of my work at very low volume, and when it's all finished I like to whack the volume up to see if it worked. I do a quick CD of it, and put the CD in my car, and then drive around the area. It's quite a good system in the car, and especially when I listen to it in a condensed space like that, and just see how it feels,…as if the thing is inside your head almost. Any discrepancy will show up there, and I'll just keep tweaking the mix until it sounds good there and on the Dynaudio Air monitors.

So are we going to see a record out by Eric Stewart?

My first solo album, "Do Not Bend," came out about three years ago. My next album is 90 percent finished, and that's going to be called "Vive la Difference." I've written a track about that. The song itself is about the fact that people are different. Why the hell should we be asking people to all be the same? I love the fact that we're different. Vive la difference! That's the sort of message in that particular track. The album again is very, very varied. Lots of heavy guitar tracks probably a guitar solo on every track, because I still love to play lead guitar. Good French drummer on there, fabulous French drummer by the name of Alain Merlingeas.

I recorded the drums at a studio near me, in France, called Spear Studios, and it's run by a fantastic guy called Pascal Escoyez. It's a Spanish name, but he's actually Belgian. He's got this fabulous studio that he's build half underground, and half not underground. It's just a giant control room. And all the instruments are around the sides of the control room. Everything, you know: Hammond organs, mellotrons, old Fender amps, guitars, everything's there. Even the drum kit is placed there, so you're all playing together in the same room as the engineer. A bit like Sam Philips would have been, or the early records from The Band, when they recorded "Big Pink." A very interesting way of doing things. You sort of feel you're involved a lot more than being on the other side of the glass in a studio. It's a different vibe. I'm very excited about that, because the last album, I used drum machines and samples. This time, I haven't done that, and it's got a bit more of that old vibe that I used to like with the 10cc records, especially the early ones where we were recording on 8-track.

We sat there for days just listening to the thing, saying "Wow, what the hell have we recorded here?

I think one of the down sides of modern recording is that we've got endless choice now, of how many tracks, and you can sit there forever, and then go back to mix one from mix 200, and you don't have to commit anything. I think it sometimes clouds the issue of what you were trying to do. So what I'm trying to do now is restrict myself to 16 tracks of recording on a computer. I've given myself a challenge: I've got to do it on 16 tracks, and if it doesn't sound right, then I've got to find a way of making it sound right, and ditch stuff from it that may be not needed. I'm being very careful with the blend of the sound on the tracks and instruments won't get in the way of each other, which can happen so easily.

One of the biggest faults I find on a lot of modern recordings is that they just blitz them with sound so heavily, you can't see the wood for the trees. Where if you listen to something gorgeous and simple, like the early Beatles tracks, or Presley, you've got three guys and one guy singing, with a bit of spring reverb or something, and it sounds beautiful and powerful. We sort of lost the ability to do that, with the technology becoming so complex, so I'm heading a bit back in that direction, and looking for that warm, warm sound. Hence the UA emulations. They are so good. Every one of them I use. The Precision EQ is gorgeous. The Pultec's fantastic. The EMT plate is just astounding, because I used to use them at Strawberry, heading down the stairs, but the 140 EMT plate is just beautiful.

Isn't it? That one was modeled after EMT plates at the Plant studio at Sausalito, California, where Sly and the Family Stone recorded, and Fleetwood Mac. So all those emulations were modeled after specific things. The Roland Space Echo was modeled after one the Talking Heads used and then the Helios was modeled after this board that was in Basing Street Studio in London that "Stairway to Heaven" was mixed on.

Yeah. I read that, yeah.

It's a great way to approach it. So how long have you been working with the UAD-1 card?

I've had the UAD-1 since they first came out. As soon as I saw the card, and I saw the graphics, I bought it. Now let me tell you, the graphics are brilliant. It's like I'm sitting in front of the real thing, if I'm looking at the screen… because I've got the real thing three feet away from me! The UAD-1 looks like it should look, it sounds like it should sound. It's awesome.

It's really nice to hear. You know, it's a small, family-run company, run by Bill Putnam, Jr. Everything is built in the United States. And they're in Santa Cruz by the beach, and you walk in and there's are surfboards and bicycles. Everybody seems to have a lot of pride in their work, especially the people on the assembly line. It's just a really nice, small, family-run company, so it's nice to have someone like you recognize the workmanship. It really means a lot.

When you talk to me about it like that, I can see it coming through in the hardware and software. I can see that thought and that feeling, and I can hear it. If you take that amount of care about something, it comes through. It wins out over just mass producing things.

If you had a dream product that UA could make for you, what would it be?

I did mention briefly, didn't I, the dbx compressors? They did have a unique sound. I've never experienced that sound with anything else. It's very different to the UREIs, and the Pultecs. But you've got everything there that I think anybody would need. You've got the Fairchild. Jesus Christ. You've got everything there. You did the Roland Space Echo.

It’s like I'm sitting in front of the real thing, if I'm looking at the screen… because I've got the real thing three feet away from me! The UAD-1 looks like it should look, it sounds like it should sound.

Maybe something silly like the Cooper Time Cube. That little thing has been used--it's a gorgeous little sound, and we used that a lot on some of our backing vocals, when they were young, before AMS came up and really brought out a fabulous digital reverb, the Cooper Time Cube was quite a unique sound. Yeah. That was beautiful. Maybe that one.

Thank you so much.

Not at all. I love to talk about music, I love to talk about recording. It is the biggest thrill for me, that somebody can sit there 25, 30 years later and say, "I got off on that track, I love that track." I have pieces of music myself, some classical music, that I never tire of listening to, like watching a great film. You could watch it a thousand times, and each time the same vibe. Music is like that. It lifts you out of your space--if you've been down, or whatever. Like a good film will make you forget for two hours that you've had a row at the bank, or your best woman just left you. It's one of those things. Music does that.

What do you listen to now? Do you listen to new rock music that's out?

I do. I listen to everything that comes out. There are bands like Coldplay, I think are pretty good.

They also have a real signature sound, and a real signature vocal sound.

It is, and it's not a complex sound. It's just a very back to roots, basic, rhythm track and vocals. They sound like they believe in themselves, like The Beatles did. It's refreshing in that way. I still do all The Beatles' stuff. And I did work quite a lot with Paul McCartney. It's terrific. And George Martin's a really good friend of mine. And he's just remixed, as you know, The Beatles tracks, in such an unusual way with his son, for the Cirque du Soleil. The album's called Love. It's beautiful. Bloody hell. It's beautiful. You listen to that and think what have they've done--how do they do that?

Have you been approached to produce any up-and-coming bands? Is it something you'd want to do?

I do get asked, but no. There's nothing I really want to go out there and do. There are peaks in your career. We had a good talk to George Martin about this. When everything is gelling somehow, it's ethereal. I don't know why it happens. But you peak in your writing. I think you peak in your vocal talent. You peak in--I wouldn't say playability of instruments, because that's something you can continue to develop 'til you drop. Like a good jazz musician or a good blues musician just gets better and better, usually. But vocals, obviously, is down to how good your throat's held up. So no, I don't want to really produce anybody else. I will write for people, if they ask me, and I do occasionally do film music, and I occasionally do TV music for people. But most of the time I'm quite happy still putting my thoughts down in a computer and singing them, and playing around with them.

|

| Eric Stewart, present day, in France. |

Eric Stewart now markets his music, including new album Do Not Bend, via the http://www.ericstewart.uk.com/ and http://www.strawberrysoundtracks.com/ web sites. Following the demise of 10cc he also produced Sad Café and ABBA's Agnetha, and worked with Paul McCartney for several years, before helming and participating in two new 10cc albums during the early '90s: ...Meanwhile and Mirror Mirror. The first of these reunited all four original members.

"There's always something new that I'm going to learn. Like new ways of dealing with people, new ways of dealing with instruments and recording things, making them sound good."

Questions or comments on this article?

updated 05-04-07