Understanding Audio Data Compression

Love it or hate it, data compression (not to be confused with audio signal compression, which is a different issue) schemes like MP3, FLAC, AAC, and other relatives have fundamentally changed music as we know it. The battle between fidelity and portability was long ago declared no contest, with convenience winning hands-down over sonic quality.

But while the ability to compress what was once a wall full of vinyl into your pocket is a boon for music consumers, it’s a bit more of an issue for those of us on the creative side of the equation. As record stores gasp for breath, and online CD sales continue to decline, artists have little choice but to make their works accessible online, and that means crunching your music.

So how to best compress without making a mess of the music you’ve worked so hard to make sound good? As with most things, the answer depends on what you’re after, and what you’re willing to compromise.

When it Comes Down to Crunch

With the Internet as our primary resource for both selling and marketing our wares, the question is no longer whether to compress, but rather how, and how much. There’s a mind-boggling alphabet soup of compression codecs available, ranging from good to barely tolerable.

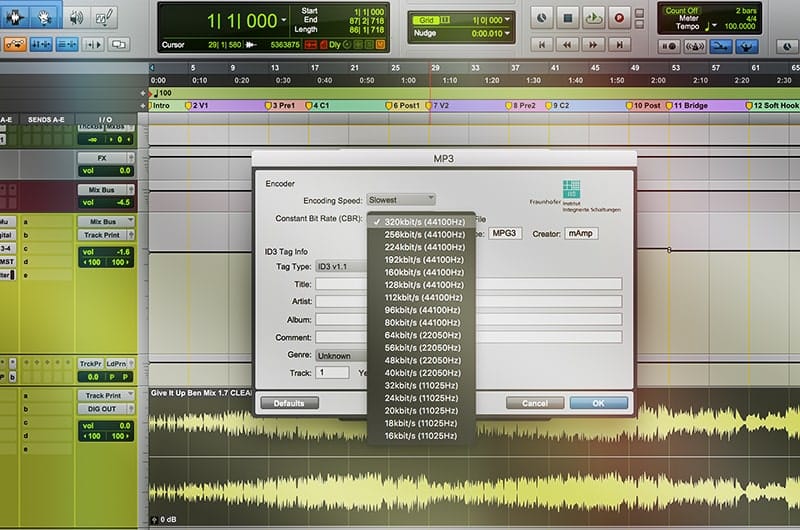

Far and away the most ubiquitous compression format is MP3 (which stands for MPEG Audio Layer III), and making your recordings available as MP3s is pretty much a given if you want maximum exposure. But not all MP3s are created equal; depending on the bitrate and other factors, an MP3 can sound nearly indiscernible from the original WAV file, or as flat and lifeless as a wet newspaper. Not surprisingly, there’s a direct trade-off between file size and fidelity.

Briefly, here’s how MP3 (and most other compression schemes) work. The process employs a combination of digital technology and the science of aural perception (psychoacoustics) to remove data bits from the original digital file that are considered to be essentially inaudible. These bits can include frequencies beyond the normal threshold of human hearing, sounds that are masked by other sounds, and various other “redundant” sonic information.

The point of contention with this whole concept is just how much of that data is truly inaudible. While some bits can be removed with little consequence, much of what gets stripped away can subtly affect our perception of how things sound. While moderately compressed files can deliver near-CD quality sound, too much compression can remove elusive qualities that can make a difference to how we perceive music on a subconscious level.

What Have You Got to Lose?

With any compression, some audio quality loss is inevitable. Very high frequencies are typically the first data to be eliminated, and while in theory these sounds are inaudible, their loss can rob your music of its subtle overtones, presence, dynamic range and depth of field.

The audio resolution and sonic quality of an MP3 is determined by the bitrate at which it’s encoded. The higher the bitrate, the more data per second of music. As you’d expect, a higher bitrate creates better quality audio, along with a larger file.

Generally speaking, 128 kbps (kilobits per second) is considered the bitrate at which an MP3 begins to exhibit artifacts of data compression. Not coincidently, it’s also the rate many websites use for downloads, since it offers a smaller file size with relatively minimal loss. Rates below 128 kbps are usually not recommended for anything other than spoken word recordings. Bitrates of 192 kbps, 256 kbps, or higher preserve most of the original sonic information, making them a better bet for music you care about.

Another alternative is to encode using a VBR, or variable bit rate. VBR examines the data as it’s encoding, using a lower rate for simple passages and a higher rate for more complex ones. While the resulting file size is smaller than using a higher bitrate, sometimes VBR encoding can end up compromising the audio fidelity of delicate material like a solo acoustic guitar or vocal.

Other Alternatives

While MP3 is the most popular data compression format, there are countless other formats available. Each uses a different type of algorithm to determine what data to discard, and the resulting differences in sound can range from subtle to fairly obvious. There are far too many different encoding formats to name them all, but here are a few of the more commonly used ones.

WMA (Windows Media Audio) was created by Microsoft, and is often offered as an alternative to MP3 on music and video download sites. It’s also common on sites that offer streaming audio and video files compatible with Windows Media Player. While many people feel the sonic quality is superior to MP3, WMA files tend to sound overly bright and brittle, with less than optimal stereo imaging.

AAC (Advanced Audio Coding) was designed to be a successor to MP3, and although it is a sonic improvement, its popularity has never really taken off. AAC is a default standard for iTunes, the iPod, the iPhone, as well as PlayStation and Nintendo DS. It’s also often used as the audio component for Apple’s QuickTime and MP4 video formats. Generally speaking, if you’re going to offer a second encoding format online, AAC is the one to consider.

AC3 is a format developed by Dolby and is often used for video soundtracks due to its superior stereo imaging and ability to handle multitrack formats like 5.1 surround. Because of this, many consumer-grade DVD players support AC3 format.

RA (Real Audio) is a fairly good-sounding codec, but is on the decline due to the fact that the files only play on Real Audio’s proprietary player. Many people refuse to install the Real Audio player due to its excessive advertising and high-CPU demands.

Ogg Vorbis is an open standard audio format that delivers a very high-quality sound. Unfortunately, like many open standard projects, it has had a hard time catching on among users.

FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec) is one of the few audio formats that delivers truly lossless compression. FLAC is similar to a ZIP file, but is designed specifically for audio. FLAC is also open-source, and FLAC files can be played back on most MP3-compatible players. (There are several other lossless formats, including Apple Lossless, WMA 9 Lossless, Monkey’s Audio and MPEG-4ALS, but none offer the open compatibility of FLAC.)

To Squash or Not To Squash

Many musicians and music aficionados bemoan the widespread acceptance of compressed audio, and rightfully so. Some recording professionals have begun to adopt the stance that, since their final product will be heard as an MP3 on low-priced earbuds, there’s little reason to bother striving for sonic excellence.

Thankfully, that attitude is still in the minority, and most artists still care deeply about the music they’re making. And for those artists, the good news is that as hard disk space continues to drop in price and broadband Internet access becomes faster and more commonly available, file sizes become less of a barrier. In fact, many musicians are now offering full WAV versions of their songs alongside MP3s.

In the end, what compression schemes you use, or if you use any at all, is strictly up to your ears and your bandwidth. The best advice is to listen very critically to whatever formats you opt for, and to select the highest quality you can. You can always compress larger files into smaller ones, but once you’re crunched those files down, there’s no way to get those bits back.

— Daniel Keller

Read More

Top 5 Reasons Mic Preamps Matter

With dozens, if not hundreds of different brands, models, shapes, sizes, variations, and configurations to choose from, it’s no wonder mic preamps are among the most misunderstood pieces of the audio signal chain.

Tips for Prepping Your Mixing Session

Here's some preparation that needs to be done before you start your mixing session.

Total Harmonic Distortion

THD stands for Total Harmonic Distortion and can be used to estimate the degree to which a system is nonlinear.